Wimbledon F.C.

|

|||

| Full name | Wimbledon Football Club | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Dons; Wombles; The Crazy Gang |

||

| Founded | 1889 (as Wimbledon Old Central Football Club) | ||

| Dissolved | 2004 (became Milton Keynes Dons)[1] | ||

| Ground | Wimbledon Common (1889–1912) Plough Lane (1912–91) Selhurst Park (1991–2003) National Hockey Stadium (2003–04) (Capacity: Wimbledon Common: unknown Plough Lane: 15,876 Selhurst Park: 26,309 National Hockey Stadium: 9,156) |

||

| League | Last league was Football League First Division | ||

| Final season 2003–04 |

24th (Relegated) |

||

|

|||

Wimbledon Football Club was an English professional football club from Wimbledon, south-west London. Founded in 1889 as Wimbledon Old Central Football Club,[A] the club spent most of its history in amateur and semi-professional non-League football before being elected to the Football League in 1977 and reaching the First Division in 1986 after a mere nine seasons in the league and just four seasons after being in the Fourth Division.

Wimbledon stayed in the First Division and then the FA Premier League from 1986 until 2000. Most famously, in 1988, Wimbledon beat the then-champions Liverpool 1–0 in the FA Cup final, thus becoming only the second football club (after Old Carthusians) to have won both the FA Cup and the FA Amateur Cup, having won the latter in 1962–63.

Following the publication of the Taylor Report, which recommended that all top-flight clubs play in all-seater stadiums, the club decided that it needed to move from its Plough Lane home in 1991. Wimbledon began to groundshare with nearby Crystal Palace, an originally temporary arrangement that ended up lasting over ten years. In May 2002, after rejecting a variety of possible new local sites, the club was granted permission to move 56 miles (90 km) north to Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire. The move away from their native south London was deeply unpopular both with the bulk of the club's established fan base and football supporters generally. The majority of supporters[2][3] responded to the planned relocation by forming a new club, AFC Wimbledon. Wimbledon moved in September 2003, and became Milton Keynes Dons in June 2004.[1]

Contents |

History

Non-League beginnings

Wimbledon Old Central Football Club was formed in 1889, taking its name from the Old Central School on Wimbledon Common where players had been pupils. The club's first match was a 1–0 victory over Westminster, and it only took seven years for success to come to Wimbledon as the club won both the Clapham League and the Herald League in 1895–96. Wimbledon won the Clapham League again in 1900–01, as well as two minor trophies. A meeting was convened on 1 May 1905, and the decision was taken to drop "Old Central" from the club's name – the club became Wimbledon Football Club, and under its new name the club won the South London Charity Cup the same year – however, excessive debts caused the club to fold in 1910. The club was restarted year later under the name Wimbledon Borough, though "Borough" was dropped from the team's name after barely a year. The club continued to play on Wimbledon Common and at various other locations in the Wimbledon area until 1912, when the side settled at Plough Lane. Wimbledon joined the Athenian League for 1919–20, and in the second season in its new division finished as runners-up.[4] The club then joined the Isthmian League. Winning four Isthmian League titles during the 1930s, and reaching the FA Amateur Cup final in 1934–35, Wimbledon began to prosper. The club reached another FA Amateur Cup final in 1946–47, and finished as runners-up in the league twice over the next few seasons. Wimbledon won the Isthmian League for the fifth time in 1958–59 before starting a period of domination that saw three successive championships – 1961–62, 1962–63 and 1963–64. Wimbledon also lifted the FA Amateur Cup in 1962–63, and following these successes the decision was taken to turn professional for the 1964–65 season and to enter the Southern League. Wimbledon had continued success in the new league, finishing as runners-up at the first attempt.[4]

Wimbledon became nationally famous during a spectacular FA Cup run during 1974–75: entering the competition at the First Qualifying Round, Wimbledon saw off first Bracknell Town, then Maidenhead United, Wokingham Town, Guildford & Dorking United, Bath City and Kettering Town to find themselves in the third-round proper. They then became the first non-League team that century to beat a First Division side away from home, as Wimbledon defeated Burnley at Turf Moor in the third-round. In the fourth-round form continued, as the team held the reigning First Division champions Leeds United to a 0–0 draw at Elland Road. Goalkeeper Dickie Guy saved a penalty from Peter Lorimer to earn a replay, which was narrowly lost 1–0 by an own goal in front of over 40,000 spectators at Selhurst Park. After winning the Southern League three times running, Wimbledon were elected to The Football League in place of Workington in 1977.[4]

The Football League

1977–78 was a satisfactory Football League debut for Wimbledon, who finished 13th in the Fourth Division.[4] Allen Batsford had resigned as manager on 2 January 1978 to be succeeded by Dario Gradi, who guided the club to promotion in 1978–79.[4] Wimbledon's first stay in the Third Division was not a successful one. The team struggled, and was relegated in bottom place, winning just 10 league games all season, after losing key players Les Briley and Ray Lewington.[4] Following relegation, relocation to Milton Keynes was considered – chairman Ron Noades entered talks with the Milton Keynes Development Corporation about the possibility of moving the club to the new town, but the plan was never executed.[5][6]

Still in south London, 1980–81 saw Wimbledon regain Third Division status at the first attempt, at the end of an eventful season which saw chairman Ron Noades walk out of the club to take over Crystal Palace, taking manager Dario Gradi to Selhurst Park with him.[4] At Plough Lane, assistant manager Dave Bassett was promoted to manager. Under Bassett, Wimbledon were relegated in 22nd place.[4] Just before the survival battle was lost, injured defender Dave Clement committed suicide.[7] Wimbledon once again regained Third Division status at the first time of asking, triumphing as Fourth Division champions in 1982–83, and in the next season the Wimbledon players continued to excel as they achieved a second promotion to the Second Division after finishing runners-up with 97 league goals.[4]

1984–85 was Wimbledon's first season in the Second Division, and everyone at the club was prepared for long and hard struggle to preserve this status. A 12th place finish was more than satisfactory for a club that was playing at this level for the first time.[4] The next year started well for Wimbledon as Middlesbrough were defeated 3–0 on the opening day of the season – the team was soon looking like a contender for promotion. Promotion in third place was sealed on the final day of the season with a victory over Huddersfield Town. Thus, Wimbledon had reached the First Division, only four years after playing in the Fourth Division and nine years after being elected into The Football League.[4]

The top-flight

Many observers tipped Wimbledon to go straight back down in 1986–87, but after losing the first game of the season away at Manchester City, Wimbledon won the next four games to perch atop the league table on 1 September. Wimbledon eventually finished sixth, before Dave Bassett moved on to Watford.[4] His successor was Bristol Rovers manager Bobby Gould. Dubbed "The Crazy Gang" because of the eccentric behaviour of its players, fans and chairman, Sam Hammam, the club's greatest moment came in 1988 when, very much against expectation, the team won the FA Cup, beating overwhelming favourites Liverpool 1–0 with a goal from Lawrie Sanchez. 37,000 Wimbledon fans witnessed captain Dave Beasant becoming the first goalkeeper to save a penalty in an FA Cup final, stopping John Aldridge's shot.[8] The only downside of this triumph was the fact that the club would not be able to compete in the European Cup Winners' Cup, as the ban on English teams from European competition following the Heysel Stadium Disaster was still in operation at this time.[9]

Just days after the FA Cup triumph, Wimbledon directors announced plans to build a new all-seater stadium in the club's home borough of Merton. In the season following the FA Cup triumph, Gould steered Wimbledon to a secure 12th place finish in the First Division, and in 1989–90 the side finished eighth.[4] Despite these successes, Bobby Gould was replaced by Ray Harford in 1990, who in the same year as Wimbledon's FA Cup triumph had guided Luton Town to victory in the League Cup. Under Harford's management, Warren Barton was purchased for £300,000 while Wimbledon had another strong season in 1990–91, finishing seventh.[4]

Nothing came of the plans for a new ground and at the end of 1990–91 the club's board decided that Plough Lane was beyond redevelopment to meet the new FA rule requiring all-seater stadia.[10] Consequently, the club moved to Selhurst Park before the 1991–92 season, ground-sharing with Crystal Palace. Harford suddenly resigned in October 1991, to be replaced by Peter Withe. Withe lasted until just after the turn of the new year, when Joe Kinnear was promoted from the role of youth team coach, initially taking over as interim manager. After guiding Wimbledon to 13th place in the First Division and booking a place in the inaugural FA Premier League,[4] Kinnear got the manager's job on a permanent basis.

1992–93 began as a struggle for Wimbledon – the club was third from bottom on Boxing Day. However, the team recovered well in the new year and finished 12th.[4] The next season was one of Wimbledon's best seasons to date as the side finished sixth in the FA Premier League and reached the quarter-finals of the League Cup.[4] Wimbledon remained hard to beat in 1994–95, finishing ninth in the league.[4] During the close season the Dons made their first and only appearance in a UEFA European competition, entering the Intertoto Cup. However, after fielding an under-strength side containing reserves, youth team players and trialists in their group stage games, the club – along with Tottenham Hotspur – were banned from Europe for the following season.[11] Not that it mattered; after losing Barton to Newcastle, 1995–96 saw a drop to 14th.[4] Wimbledon made a fine start to the 1996–97 campaign – after losing the first three fixtures, the players proceeded to win their next seven and reach the summit of the FA Premier League. There was delight in early February when they eliminated Manchester United from the FA Cup – Wimbledon reached both the FA Cup semi-finals and the semi-finals of the League Cup. Wimbledon's last hope of qualifying for European competition now lay with a challenge for a top-five league finish, but the team could only manage eighth.[4]

Decline and move

1997–98 looked highly promising for Wimbledon as late on as Christmas, as the team was regularly in the top five. However, the side's form in the second half of the season was less impressive, and the club dipped to 15th place in the final table – the lowest finish yet for Wimbledon in the top-flight.[4] A similar pattern followed in 1998–99 – a good start followed by a slump. As late on as mid-March, the team was on the fringe of a UEFA Cup place. The signing of West Ham United striker John Hartson boosted hopes of success for Wimbledon, but a terrible run of form in the final weeks of the season saw the side dip to 16th in the final table.[4] Wimbledon again reached the League Cup semi-finals that season – losing to eventual winners Tottenham Hotspur.[4]

Joe Kinnear stepped down as manager in June 1999 due to ill health, and was succeeded by Norwegian coach Egil Olsen. With John Hartson leading the attack, fans were confident that the club could finish much higher this season, and possibly challenge for honours. A strong challenge came in the League Cup, where Wimbledon reached the quarter-finals. Wimbledon's league form had slowly deteriorated in the second half of the season, and Olsen had left in early May with relegation now looking a real threat. Long-serving coach Terry Burton took over,[12] but on 14 May 2000, 12 years to the day after the FA Cup win, the side was relegated from the top-flight after a 14-year stay due to a 2–0 defeat at Southampton. A 1–0 win for fellow strugglers Bradford City over Liverpool sealed relegation for Wimbledon.[4]

Burton remained manager of Wimbledon for two seasons in the second tier before he was controversially sacked at the end of 2001–02 after the club had narrowly missed out on the promotion play-offs two seasons in a row.[4] The move to Milton Keynes was announced in August 2001,[13], and despite opposition from the majority of Wimbledon fans,[14] The Football League[14] and The Football Association,[14] was given permission by an independent commission on 28 May 2002.[14][15] AFC Wimbledon was founded in response to this,[2][3][16] and much of Wimbledon's support flocked to the new club.[2][3][16] Goalkeeping coach Stuart Murdoch was promoted to manager,[17] and as attendances plummeted,[18] Murdoch's team finished tenth during the club's last full season at Selhurst Park.[4] Wimbledon entered administration in June 2003,[19] and the relocation went through in September.[20] Although crowds improved at the club's new base, the administrator sold any player who could command a transfer fee and Murdoch's team finished bottom.[4][21] The club was brought out of administration at the end of the season,[22] and subsequently rebranded as Milton Keynes Dons.[1][22]

Move to Milton Keynes

Origins

1979 proposal

Because of the club's "fairytale"[23] rise from obscurity to England's top-flight, the team quickly "outgrew"[23] their Plough Lane ground.[23] As early as the late 1970s, soon after the club's election to The Football League in 1977, Wimbledon chairman Ron Noades claimed to have "[seen] the limitations in Plough Lane" and cited the club's location as the reason for the club's continuing low gates.[5] As a result, Noades considered moving the team to Milton Keynes,[5] the new town in Buckinghamshire, 56 miles (90 km) away.[5] In English football, the relocation of teams away from their traditional districts is extremely unusual because of nature of the relationship between clubs and their local fans: the local football club is regarded by most English football supporters as part of the local identity and social fabric rather than as a business that can be transplanted by its owners at will. As a result, any relocation plan would be strongly opposed by fans in the club's original area, and unlikely to succeed in most new locations due to the existence of established local clubs in most towns and cities that would already have secured the loyalty of local supporters. However, due to its recent establishment in 1967, Milton Keynes provided an exception to this rule; most people living there had been born and raised elsewhere,[24] and no local team had yet risen high enough in the football pyramid to secure their loyalty.[25]

Noades's interest was attracted by the site designated by the local Milton Keynes authority for a stadium next to the town's still-under-construction Central railway station.[5] Intending to merge Wimbledon with a local Milton Keynes club in order to take up the site, Noades bought non-League club Milton Keynes City for £1,[26] capitalising on the smaller club's financial problems.[5] However, as a result of his belief that gates would not improve by much were Wimbledon to move there, he did not go through with the plan, instead choosing to sell Milton Keynes City on.[5][6] Noades, who had paid £2,782 for then non-League Wimbledon in 1976,[27] charged Sam Hammam a figure between £40,000 and £100,000 for the club in 1981 before becoming chairman of nearby Crystal Palace during the same year.[26][27]

Wimbledon leave Plough Lane

After reaching the First Division for the 1986–87 season,[4] Wimbledon's success as a club in the top-flight of English football was founded on unorthodox financial management and judicious dealings in the transfer market.[16] The team was granted planning permission to build a 20,000-capacity all-seater ground in its home borough of Merton in 1988,[23] but the site was instead made into a car park by a newly-elected Labour council in 1990.[23] Wimbledon's desire to move was made a necessity a year later, when the Taylor Report, which ordered the extensive redevelopment of football grounds, was released.[23] When Hammam had purchased the club from Ron Noades, Wimbledon had also owned its ground at Plough Lane,[26] though a pre-emption clause had existed specifying that the ground was only to be used for "sports, leisure or recreational purposes"[26] – if Wimbledon Football Club was ever to cease to exist, then Merton Council would be able to buy Plough Lane back for £8,000.[26] Although this clause reduced the possibility of the club losing its home stadium, Hammam argued that it also incurred upon his ability to borrow money needed to redevelop the ground.[26] Seeking to increase the value of Plough Lane, Hammam entered into negotiations with the council for its removal in 1990; the eventual agreed price for the revoking of the clause was a sum between £300,000 and £800,000.[26] The deal had not been unanimously popular among the owners of Wimbledon – at least one club director had resigned his position in protest.[26] Despite the decision to remove the clause, the club could not afford to redevelop Plough Lane when required to do so the following year.[23]

As a result, Wimbledon moved across south London before the start of the 1991–92 season to share the Selhurst Park ground belonging to Noades's Crystal Palace.[23] This decision was unpopular among Wimbledon fans, and the club's "already modest"[23] support resultantly took a hit the club could ill-afford.[23] Concurrently with this move, the council's recommended proposal of a relocation to a ground in nearby Beddington fell through.[23] With the inflation in costs brought on by the foundation of the FA Premier League in 1992, the club soon began to lose money heavily;[16] Hammam attempted to find a new home for the club, and citing what he claimed was "a lack of support" from the local council, sought to relocate within south London to first Tolworth, then Brixton.[23] In fact, Wimbledon Stadium was offered to the club for redevelopment in 1992, but the opportunity was spurned by Hammam.[23] Two years later, after Merton Council refused to sanction Hammam's proposed sale of Plough Lane for a supermarket redevelopment, attempting to retain the site for public use, Hammam vowed, in a fit of pique, "never to return to the ground".[23]

Hammam gradually withdraws

While remaining at the club in an advisory role, Hammam sold the club to two Norwegian businessmen, Kjell Inge Røkke and Bjørn Rune Gjelsten, in 1997,[28] and, with political control of Merton Council having changed, he secured the £8 million sale of the Plough Lane site to Safeway supermarkets in 1998.[26] Hammam unsuccessfully attempted to gain permission to redevelop a former gas works in Merton during the same year,[26] and soon after once again launched abortive negotiations over a site in Beddington.[26] Following this, Hammam started to look further and further afield,[16] and despite the anger from a majority of supporters,[16] considered Dublin, Belfast and Cardiff as potential new locations for the club,[2][23] even receiving Premier League approval for the Dublin proposal before the idea was vetoed by the Football Association of Ireland.[26] Hammam then offered to buy Selhurst Park from Noades, still the owner of the ground despite his sale of Crystal Palace in 1998;[27] Hammam offered £12 million in 1999, but this plan came to nothing.[26] Hammam subsequently sold his shares in Wimbledon in February 2000,[29] and became the owner of Cardiff City in September of that year.[30]

Milton Keynes proposed again

The club was approached by the Milton Keynes Stadium Consortium, fronted by Pete Winkelman and backed by Asda (a subsidiary of Wal-Mart),[31] in late 2000.[26] This consortium proposed a large development in Milton Keynes, including an Asda hypermarket,[32] a 30,000-capacity football stadium,[32][33] a hotel,[33] a conference centre and a retail park.[26][32][33] The decision to build such a ground was complicated by the fact that the highest ranked team in the town, Milton Keynes City (a different club to the one previously owned by Noades),[25] was playing in the then eighth-tier Spartan South Midlands League, four divisions below The Football League.[25] The developers could not justify building a stadium of such a size for a club of this small stature,[31] though the system of promotion and relegation used in English football means that consistent good performance can result in a side rising through the leagues over time – indeed, as Wimbledon did themselves during the 1970s and 1980s.[4] However, the Milton Keynes Stadium Consortium resolved instead to "import" an established Football League club to use the ground.[31] Wimbledon supporters opposed to the move claimed that the stadium was a "Trojan Horse" only included in the blueprint to bypass planning rules,[31] and that although the consortium described the Asda superstore as an "enabling development to finance the building of the stadium", the opposite was in fact the case;[31] they claimed that this was why it was so necessary for the consortium to import a team: without a professional club, the ground would not be built, and without the ground, the development could not go ahead.[31] The local Milton Keynes authorities favoured the plan: council leader Norman Miles stated that "[the town] would welcome a major football club", but also implied that the identity of any relocated club was irrelevant by intoning that "[i]t could be Southend or Blackpool I suppose".[34] The consortium had already attempted to relocate Luton Town to Milton Keynes earlier that year,[35][36] but had been blocked by a Football League decree that "all clubs must stay in their own area".[36] After this, the consortium tried to negotiate a move with north London club Barnet, but failed in this also.[36]

The consortium's offer was initially turned down by Wimbledon,[26] but Charles Koppel, the new chairman appointed by the Norwegian owners in January 2001,[37] was in favour of the move.[26] Koppel claimed that the club's owners were subsidising it to the tune of "around £6 million a year" and that "if the club d[id] not move [it] w[ould] die".[26] The Milton Keynes consortium, meanwhile, had turned its attention to west London club Queens Park Rangers – just as the consortium had always maintained that the Wimbledon name, colours and badge would remain even after any potential relocation,[38] QPR were promised that the club name and blue-and-white hooped strip would be kept if the team moved.[31] QPR were also offered "supporter representation on the [club's] board".[31] Despite being in financial administration, QPR turned down the offer made by the consortium at the end of the 2000–01 season,[26] leading the consortium to once again contact Wimbledon in June 2001 with a "firmed up" proposal.[26] With Koppel now in charge, the club was more receptive to the idea.[26] As talks progressed, Winkelman began to register various internet domain names relating to "MK Dons",[31] and approached the owner of Milton Keynes City, attempting to buy the club name.[31] Although fans were "angrily opposed to the plans",[13] Koppel announced in August 2001 that the club intended to relocate to the new town;[13] the club made a formal application for the Football League’s approval at the same time.[15] Meanwhile, the local council claimed that Noades had agreed to sell the Selhurst Park ground to Wimbledon – something which Noades denied.[26]

The proposed move to Milton Keynes was opposed in most quarters: a majority of Wimbledon fans "fiercely opposed" it, as well as both The Football Association and The Football League.[14][15][16] The League told the consortium that any Milton Keynes club would have to earn membership by "progress[ing] through the pyramid" and unanimously rejected Wimbledon's application to move.[15][34] However, when the decision was contested by the club, an arbitration panel was formed, made up of Association vice-chairman David Dein (also vice-chairman of Arsenal), York City chairman Douglas Craig and Charles Hollander QC.[15][39][40] Before the arbitration panel heard Wimbledon's appeal in January 2002, Winkelman claimed that even if the move was turned down, "[the] door w[ould] be open to any club in trouble [to attempt to relocate to Milton Keynes]";[41] however, the panel unanimously decided that the decision taken had "not been properly taken in the legal sense, and that the procedures had not been fair",[15] meaning that the possibility of Wimbledon relocating remained open.[15] As a result of this verdict, the League board reconvened on 17 April 2002 to reconsider the proposal, and concluded that the matter should be considered by an independent commission appointed by The Football Association.[15] The commission members chosen by the FA were solicitor Raj Parker, FA Council member Alan Turvey (also Chairman of the Isthmian League) and Steve Stride, the Operations Director at Aston Villa.[15] The commission ruled in favour of the move, by two votes to one, on 28 May 2002.[14][15]

Relocation of Wimbledon F.C. and foundation of AFC Wimbledon

|

|

|

|

Wimbledon F.C.'s final home matches were played at the National Hockey Stadium in Milton Keynes (left), while AFC Wimbledon (right) was founded by former Wimbledon F.C. fans in protest at the relocation.

|

||

The FA made it clear that although the decision was final and binding, it strongly opposed the relocation.[14] The Association's Chief Executive, Adam Crozier, publicly stated that it was an "appalling decision",[42] while the Association itself revealed that it had submitted to the commission its opposition to the move.[14] Many Wimbledon fans were "left devastated by the decision",[14] and, calling it the "death of [their] club",[14] founded their own team, AFC Wimbledon, weeks after the move's approval.[16] Meanwhile, Wimbledon F.C. became pejoratively nicknamed "Franchise F.C.".[2] AFC Wimbledon quickly soaked up the majority of Wimbledon F.C.'s local support,[2] and this situation meant that during the 2002–03 season, Wimbledon F.C.'s last full term at Selhurst Park, attendances at Wimbledon F.C. matches fell below those at AFC Wimbledon due to the fact that most local fans were now following AFC Wimbledon instead.[2][18] Wimbledon F.C.'s resultant lower income contributed to the club entering administration at the end of that season.[3][19] While Wimbledon F.C. prepared to relocate, Milton Keynes City went out of business in July 2003 due to a lack of investment.[43][44]

After starting the 2003–04 season at Selhurst Park, the first Wimbledon F.C. match in Milton Keynes was played on 27 September 2003 – a 2–2 draw with Burnley at the National Hockey Stadium, temporarily converted for football use owing to the absence of the new stadium.[20][21] The club struggled both on and off the pitch throughout the season, spending its entirety in administration and eventually finishing bottom of the second-tier First Division.[4][21][45] An article appeared in British journal Property Week in May 2004, after Wimbledon F.C. had been relegated,[4][21] stating that the construction of the new stadium would be cancelled were Wimbledon F.C. to go out of business;[45] in response, Richard Foreman, a director of the consortium's development consultant, stated that "the scheme w[ould] go ahead"[45] with "the total support of the council"[45] were this to happen.[45] On the subject of who would occupy the new stadium, Foreman added that the consortium would "have a year and a half to find another club [to relocate to Milton Keynes]".[45] Winkelman's consortium brought the club out of administration in June 2004,[22] and although it had originally stated that the name "Wimbledon F.C." would remain in place regardless of the move,[38] changed the club's name, badge and colours soon after.[1]

Aftermath

|

|

| AFC Wimbledon's original colours |

|

|

| Milton Keynes Dons' original colours |

Identity

The new name of the club was "Milton Keynes Dons Football Club",[1] a name made up of the team's new location and a common nickname of Wimbledon-based sports teams, "The Dons". Winkelman's consortium claimed that the name was intended to "represent the past, present and future and place the club at the heart of its new community"[1] as well as to "retain a link with its former identity".[1] The blue and yellow colours that Wimbledon F.C. players had worn were replaced by an all-white strip,[46] while the club badge became an rendering of the letters "MK", the "K" positioned below the "M", rotated 90° anti-clockwise and defaced with the year "MMIV" (2004).[46] AFC Wimbledon, meanwhile, founded in 2002 to attempt to continue the original club's identity,[2][3] adopted a home kit of blue and yellow,[47] emulating the uniform worn by Wimbledon F.C.[48] In a similar vein, the emblem chosen by AFC Wimbledon was, like the Wimbledon F.C. badge, based on the coat of arms of the Municipal Borough of Wimbledon,[47] and the traditional local nickname, "The Dons", was established as the club's nickname.[47]

The new stadium

After first playing at the National Hockey Stadium in September 2003,[49] the club continued to use the ground following its June 2004 rebranding. Work on the "Denbigh Stadium" had not yet even begun; despite its original proposed opening time of the 2004–05 season, ground was not broken on the intended 30,000-capacity stadium until February 2005.[50] After the club set a new target of January 2007 in December 2005,[51] February 2007 saw a revised proposal of a 22,000-seater ground ready in July of that year, with provision for expansion to 32,000.[52] The first match at the ground, by now renamed "Stadium:mk" was played in July 2007.[53]

History and honours

The location of the history and legacy of Wimbledon F.C., as well as the honours won by the club, remained open to debate for five years after the relocation's confirmation on 28 May 2002.[54][55] In the view of AFC Wimbledon and its supporters, "[t]he identity of a football club is implicitly bound up in its community",[54][56] while on the other hand, Pete Winkelman claimed in November 2004 that "we're the real child of Wimbledon".[55] By now chairman of Milton Keynes Dons, Winkelman said during the same interview that "both the MK Dons and AFC Wimbledon share the same heritage",[55] but also that the founders of AFC Wimbledon had "left their team before their team left them".[55] Winkelman went on to say that he would retain the trophies and history of Wimbledon F.C. in Milton Keynes, because AFC Wimbledon had "abdicated their right to it when they all walked away."[55] Despite Winkelman's claims, the history and honours eventually found their way back to Merton in August 2007, a year after extensive negotiations had been completed between the WISA, Milton Keynes Dons F.C., the Milton Keynes Dons Supporters Association and the Football Supporters Federation.[57] Milton Keynes Dons announced at the same time that they considered themselves to be a new club, formed in 2004, and renounced all claims to a club history before this point.[57] As a result of these developments, the WISA revoked its call for supporters to boycott Milton Keynes Dons matches played in Milton Keynes and removed its objection to Milton Keynes Dons fans joining the Football Supporters Federation.[57] The Wimbledon F.C. trophies and memorabilia were subsequently put on public display at Morden Library in Merton in April 2008.[58]

Players and staff

The Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association, by now affiliated to AFC Wimbledon, formed the Wimbledon Old Players Association in September 2005 "as part of its campaign to reclaim the history of Wimbledon Football Club for AFC Wimbledon and/or the community of Wimbledon".[59] Membership was opened to any former Wimbledon F.C. or AFC Wimbledon player or manager; there were sixty founder members.[59] The AFC Wimbledon-backed WOPA team competed as Wimbledon in the London Masters tournament in July 2006.[60]

Club identity

|

|

| The kit worn in the 1988 FA Cup Final |

The club's nickname was the Dons, though the club was also frequently referred to as the Wombles from the mid 1970s onwards. Following the FA Cup victory in 1988, the term Crazy Gang also started to be applied; originally to the players, though over time to the club as a whole.[48] The club's mascot between 2000 and 2003 was a Womble, named Wandle the Womble. However, following the relocation, the owners of the Wombles brand refused to renew the license agreement. Three years later, a deal was agreed that saw a similar character named Haydon the Womble appear at AFC Wimbledon.[61]

The colours most associated with the club were blue and yellow.[48] The club's first colours were navy blue and white,[48] though the kit changed several times soon after the club's foundation, between combinations of: brown and blue striped shirts with navy blue shorts; green and white striped shirts with navy blue shorts; green shirts and black shorts; white shirts with navy blue shorts, and finally green and black striped shirts with black shorts.[48] Royal blue shirts with navy blue shorts and socks were finally settled upon in 1918, initially bearing a "W" (for Wimbledon) in the centre of the chest.[48] Wimbledon players then regularly wore royal blue shirts with black shorts and socks until a shift in the 1950s saw the shorts change from black to white.[48] A combination of blue shirts, blue shorts and white socks was introduced in 1966,[48] before being abandoned a year later in favour of an all-blue outfit.[48] The white socks returned in 1970.[48] A blue and yellow combination was first used in 1975,[48] but was replaced after a year with an all-white outfit trimmed with blue,[48] and this was the kit in which the club played its first season in the Football League. In 1978, Yellow shirts, blue shorts and yellow socks were adopted,[48] before the club made the change to an all-blue strip with yellow markings in 1981.[48] The kit underwent only minor changes until 1993,[48] when the a much darker blue reminiscent of the club's original kit replaced the shade that had been used for the previous twelve years.[48] Wimbledon wore these colours for the remainder of their history.[48]

The first crest the club wore was the emblem of the London Borough of Merton. This emblem appeared on Wimbledon shirts from the late 1920s until the mid 1950s, when no badge was worn.[48] The Merton coat of arms returned in the early 1970s,[48] before the club adopted its own badge on election to The Football League in 1977.[48] The crest was based on the coat of arms of the Municipal Borough of Wimbledon, and was very similar to the badge used on the club's dissolution – the difference being the inclusion of white rather than yellow. Yellow replaced white in 1981, and the same logo was used for the rest of the club's history.[48]

Wimbledon's first shirt sponsors were the club's own fund raising lottery scheme, "Golddigger", whose name appeared on the players' shirts during the 1980–81 season. Subsequent sponsors were Crispin (1983–84), John Lelliott (a building company owned by one of the Club's directors; 1984–85), Truman (1986 to 1988), Carlsberg (1988–89), Samsung (1989 to 1991), LBC (1993–94), Elonex (1994 to 1999), Tiny Computers (1999 to 2001), Maxmuscle (2001–02) and GO-MK (2002 to 2004).[48]

Stadia

Wimbledon originally played on Wimbledon Common, using the Fox and Grapes public house in Camp Road as the team's headquarters and changing room. The club moved to Plough Lane in September 1912. During the 1930s and 1940s, crowds of between 7,000 and 10,000 were not uncommon at the ground. Wimbledon's highest attendance at the ground came on 2 March 1935, when 18,080 people were attracted to an FA Amateur Cup tie against HMS Victory. However, the ground was basic, and even after the club's rapid rise to the First Division Plough Lane had changed little from Wimbledon's amateur days. The only notable difference was the addition of floodlights, first used on 3 October 1960 in a London Charity Cup match against Arsenal. At the time of the club's acceptance into The Football League, applicants had only to meet minimal stadium criteria, and once in the League these same criteria sufficed whether the club subsequently found itself in the Fourth or First Division. Following the Hillsborough disaster and the Taylor Report, the football authorities introduced strict rules giving top-flight clubs specific deadlines by which to redevelop terraced grounds or to build new all-seater stadia. The board of the club decided that Plough Lane could not be made to comply with this economically and, in 1990, announced plans to temporarily groundshare with Crystal Palace at Selhurst Park.

Given Plough Lane's location at the junction of two major roads and beside the River Wandle, major redevelopment of the site as a modern all-seater stadium would have been difficult, although not impossible. The club maintained that it had "searched exhaustively with Merton Council" for a site in or around Merton on which to build a new stadium, looking at "14 different sites over a period of five years", in addition to commissioning feasibility studies of both Plough Lane and Wimbledon Stadium. Despite this, nothing became of the club's promise to redevelop the site or find a new ground in the borough and they remained at Selhurst Park.[62]

Wimbledon's first match at the National Hockey Stadium in Milton Keynes was played on 27 September 2003.[20] The club remained there for the rest of its final season, and the ground became the first home of Milton Keynes Dons.

Supporters

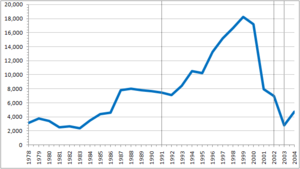

First vertical line (from left) – move to Selhurst Park (1991)

Second – foundation of AFC Wimbledon (2002)

Third – move to the National Hockey Stadium (2003)

Due to Plough Lane's modest capacity and Wimbledon's unprecedented rise from non-League football to the First Division in under ten years, the club had a much lower level of support than its top-flight rivals. During Wimbledon's first season in The Football League, Wimbledon's average attendance was only 3,135 – however, by the club's appearance in the top-flight nine years later the average attendance had risen by 149% to 7,811. Attendances did not immediately change much following the move to Selhurst Park in 1991 – however, the larger capacity gradually started to be used. Average crowds peaked at 18,235 in 1998–99, and during the next season, the team's final year in the FA Premier League, home crowds averaged 17,157. With relegation, attendances dropped catastrophically to an average of only 7,897 during 2000–01. Wimbledon averaged 6,961 during the final season before the relocation was confirmed.[63]

Following the sanctioning of the relocation to Milton Keynes, most of the team's support left to AFC Wimbledon,[2][3] the new club founded by Wimbledon supporters in specific protest at the move.[2][3] During the 2002–03 season, AFC Wimbledon's first and Wimbledon's last full season in south London, average crowds at the new club were actually higher than those at the original, though still lower than those taken at Wimbledon matches before the relocation's confirmation.[63] Attendances during the 2003–04 season, Wimbledon's last, were higher than those at AFC Wimbledon: Wimbledon averaged 4,751 at the National Hockey Stadium, compared to AFC Wimbledon's 2,606.[63]

The club had two main supporters groups – the Wimbledon F.C. Official Supporters Club and the breakaway Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association, founded in 1995.[64] The WISA was instrumental in the formation of The Dons Trust in March 2002;[64] this trust, created in part to attempt to prevent the move to Milton Keynes,[65] helped the WISA to found AFC Wimbledon months after its own establishment.[64][65] Both the WISA and The Dons Trust from this point became affiliated to AFC Wimbledon.[64][65]

The club's main rivals were considered to be fellow south London club Crystal Palace and west London-based Chelsea; however, neither of these rivalries was seriously reciprocated.[66]

Records and statistics

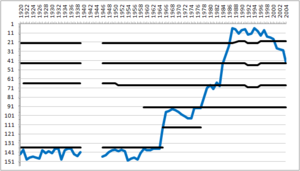

Horizontal black lines represent (from top):

1 (post-1992) – Premier League

2–3 (1–3 pre-1992) – The Football League

4–5 – Southern Football League

6 – Athenian League; Isthmian League

The record for most appearances for Wimbledon was held by Roy Law, who turned out for the club 644 times between 1958 and 1972;[67] Law's 433 league appearances was also a record.[67] Wimbledon's all-time top goalscorer was Eddie Reynolds, who scored 340 goals in 329 matches between 1957 and 1966.[68] The closest to Reynolds's record was Ian Cooke, who notched 297 between 1964 and 1977;[69] Cooke also made the second highest total number of appearances for the team, having appeared 615 times in a Wimbledon shirt.[69]

The records for most appearances and goals for Wimbledon in The Football League were both held by Alan Cork. Cork scored 145 league goals for the club in 430 matches.[70] Cork also held the record for most Football League goals in a season, with 29 during 1983–84.[70] Wimbledon's most capped player was Kenny Cunningham, who was capped 16 times for the Republic of Ireland during his time at the club.[71] Wimbledon's most expensive signing was John Hartson, for whom the club paid West Ham United £7.5 million on 15 January 1999.[71][72] The highest fee that the club received was the £7 million Newcastle United parted with to sign Carl Cort on 6 July 2000.[71][73]

Wimbledon's best win was a 6–0 league victory over Newport County on 3 September 1983,[71] while the worst defeat was an 8–0 League Cup defeat at Everton on 29 August 1978.[71] Wimbledon's longest unbeaten league run was 22 matches between 15 January and 14 May 1984;[74] the longest league run without a win, 14, was set between 19 March and 28 August 2000.[74] Wimbledon's longest run of league wins was seven, set between 9 April and 7 May 1983 and matched from 4 September to 19 October 1996.[74] Wimbledon's longest run of league defeats was the eleven matches lost in a row from 10 January to 27 March 2004.[74]

Wimbledon's highest attendance, 30,115, was set on 9 May 1993 for the FA Premier League match against Manchester United at Selhurst Park.[71]

European Record

| Season | Competition | Round | Club | Home | Away | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | UEFA Intertoto Cup | Group Stage | Bursaspor | 0-41 | ||

| Košice | 1-1 | |||||

| Beitar Jerusalem | 0-01 | |||||

| Charleroi | 0-3 |

1These matches were played at Brighton and Hove Albion's Goldstone Ground as Selhurst Park was unavailable.[75]

Players

Wimbledon's final squad

- The squad given here is made up of the players registered to the club on the date of Wimbledon F.C.'s final league match (Wimbledon 1–0 Derby County, 9 May 2004). Updated 9 May 2004.[76]

Note: Flags indicate national team as has been defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

- a ^ Denotes players who later played for Milton Keynes Dons[c]

- b ^ Denotes players who later played for AFC Wimbledon[c]

- c ^ Sourced to Soccerbase.

Notable former players

Managers

Prior to the appointment of H. R. Watts as first team manager in 1930, a committee would deal with first team affairs, such as choosing the team on a matchday.[77] Doc Dowden was appointed manager in 1946,[78] and stayed in the position until leaving at the end of the 1954–55 season.[79] Les Henley arrived in his place as first team coach,[79] and stayed at the club for sixteen years in which the club progressed immensely, winning the FA Amateur Cup as well as three Isthmian League championships before turning professional and moving to the Southern League.[80][81] However, in 1971 Henley was replaced by Mike Everitt, who arrived as player-manager. After two seasons, Everitt left to manage Brentford and Dick Graham arrived as a replacement. Graham remained until March 1974, and a replacement was not appointed until July of that year, when Allen Batsford was made manager. Batsford led Wimbledon to The Football League, but resigned only half-way through the first League season.[81] Dario Gradi was made manager three days later,[81] but after three seasons he too resigned.[82] His replacement was Dave Bassett, who took Wimbledon to sixth in the First Division before moving to Watford.[82] Bobby Gould spent three years as manager before being replaced by Ray Harford, who spent just over a season with Wimbledon. After Harford, Peter Withe had a spell as manager lasting only three months. Joe Kinnear was brought in during January 1992, and managed the club until leaving in 1999 due to ill health. A season was spent under Egil Olsen in which the team was relegated from the FA Premier League before Terry Burton was made manager.[12] Burton's Wimbledon narrowly missed the play-offs twice in a row before he was sacked. Stuart Murdoch managed Wimbledon for the club's final two seasons.[17][83]

- Statistics apply to competitive league and cup matches only. Wartime matches excluded.

| Name | Nationality | From | To | Matches | Won | Drawn | Lost | Win % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H.R. Watts | 1930 | 1946 | [77][78] | ||||||

| Doc Dowden | 1946 | August 1955 | 375 | 186 | 64 | 126 | 49.6 | [78][79] | |

| Les Henley | August 1955 | 5 April 1971 | 869 | 468 | 156 | 235 | 53.9 | [79][81] | |

| Mike Everitt | 5 April 1971 | 6 August 1973 | 120 | 49 | 26 | 45 | 40.8 | [81] | |

| Dick Graham | 18 August 1973 | 16 March 1974 | 45 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 35.6 | [81] | |

| Allen Batsford | July 1974 | 2 January 1978 | 231 | 131 | 51 | 49 | 56.7 | [81] | |

| Dario Gradi | 5 January 1978 | 24 January 1981 | 171 | 63 | 47 | 61 | 36.8 | [81] | |

| Dave Bassett | 31 January 1981 | 17 June 1987 | 303 | 144 | 74 | 85 | 47.5 | ||

| Bobby Gould | 26 June 1987 | 18 June 1990 | 142 | 57 | 43 | 42 | 40.1 | ||

| Ray Harford | 18 June 1990 | 7 October 1991 | 56 | 20 | 17 | 19 | 35.7 | ||

| Peter Withe | 7 October 1991 | 19 January 1992 | 17 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 5.9 | ||

| Joe Kinnear | 19 January 1992 | 9 June 1999 | 364 | 130 | 109 | 125 | 35.7 | ||

| Egil Olsen | 9 June 1999 | 1 May 2000 | 43 | 11 | 12 | 20 | 25.6 | [12] | |

| Terry Burton | 1 May 2000 | 25 April 2002 | 108 | 39 | 39 | 30 | 36.1 | [12] | |

| Stuart Murdoch | 25 June 2002 | 7 August 2004 | 101 | 30 | 17 | 54 | 29.7 | [17][B] |

Managers from Dowden until Batsford sourced to: Jones, Marc. "AFCW Statistics". FOTO. http://afcw.foto.co.uk/. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

Managers after Batsford sourced to: "Manager History for Wimbledon". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. http://www.soccerbase.com/manager_history.sd?teamid=2812. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

Honours

Wimbledon were a successful club even before election to The Football League, winning eight Isthmian League titles (including three in a row from 1962 to 1964) and three successive Southern League titles (from 1975 to 1977). Having also won the FA Amateur Cup in 1963, the run of Southern League titles prompted Football League election in 1977.[4]

Even at the higher level, Wimbledon continued to collect honours; the most notable being the FA Cup victory in 1988, which made Wimbledon only the second club to have won both the FA Cup and its amateur equivalent. Despite swift success in The Football League, the club's rapid ascent combined with short spells in the Second and Third Divisions meant that the team only won a solitary divisional championship within the League – the Fourth Division title of 1982–83.[4]

| Honour | Year(s) | |

|---|---|---|

| Football League Second Division | promotion | 1985–86 |

| Football League Third Division | promotion | 1983–84 |

| Football League Fourth Division | champions | 1982–83 |

| promotion | 1978–79, 1980–81 | |

| FA Cup | winners | 1987–88 |

| FA Amateur Cup | winners | 1962–63 |

| runners-up | 1934–35, 1946–47 | |

| Football League Group Trophy | runners-up | 1980–81 |

| Anglo-Italian Cup | runners-up | 1975–76 |

| Southern Football League | champions | 1974–75, 1975–76, 1976–77 |

| runners-up | 1967–68 | |

| Isthmian League | champions | 1930–31, 1931–32, 1934–35, 1935–36, 1958–59, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64 |

| runners-up | 1949–50, 1951–52 | |

| Athenian League | runners-up | 1920–21 |

Footnotes

- A. ^ The club itself was called "Wimbledon Old Central Football Club", while the team was collectively referred to as "Wimbledon Old Centrals".

- B. ^ Stuart Murdoch managed Milton Keynes Dons after the club's rebranding. 7 August 2004 is the date of Milton Keynes Dons's first league match, and so is given as the date on which Murdoch ceased to manage Wimbledon.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Wimbledon become MK Dons FC". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). 2004-06-21. http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2004/jun/21/newsstory.mkdons. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Heller, Ivor (2002-09-01). "Wombles are on their way". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2002/sep/01/sport.comment7. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Pryce, Robert (2002-08-26). "The Dons flow in front of the few". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2002/aug/26/match.sport1. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 Rundle, Richard. "Football Club History Database - Wimbledon". Football Club History Database. http://fchd.info/WIMBLEDO.HTM. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Noades, Ron (2001-04-01). "I looked at MK in the 70's". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/olmedia/1100000/audio/_1101075_noades_dons.ram. Retrieved 2009-05-30. "I certainly looked for alternatives for rehousing Wimbledon, I mean, I could see the limitations in Plough Lane; but the big problem with Wimbledon was, in my view, was that Richmond Park was several square miles of parkland, where there weren't any houses, and it affected Wimbledon's gates compared to other clubs. Yes, we took an interest in Milton Keynes … we took a controlling interest in Milton Keynes, at the time they had financial problems, and I went up there, I was in the local press, I met the local authority, and they had a stadium site, right next to the big bus terminal there and the station, the main line route from Euston up to Manchester, and they were very keen to get a Football League club, effectively a franchise if you like, into Milton Keynes to take up that site. … I couldn't really see us getting any bigger gates than what Northampton Town were currently getting at that time, and, in fact, are still getting. I really couldn't see any future in it. I can't actually see that there is a means of drawing large attendances to Milton Keynes."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Crabtree, Stephen (April 1996). The Dons in the League 1977–1982. Buckingham: Sporting and Leisure Press. ISBN 0860235580.

- ↑ "QPR offer Clement emotional Loftus Road deal". Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers. 2007-09-12. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-481428/QPR-offer-Clement-emotional-Loftus-Road-deal.html. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "Classic Cup Finals: 1988". The Football Association. http://www.thefa.com/TheFACup/FACompetitions/TheFACup/History/HistoryOfTheFACup/1988WimbledonLiverpool.aspx. Retrieved 2009-08-24. "Outsiders at 33-1 before the third-round in January, Wimbledon turned the form book upside down to beat Liverpool, recently crowned League champions and one of the hottest favourites for years[.] … Beasant … was responsible for two FA Cup Final 'firsts' as he became the first goalkeeper to receive the Cup and the first to save a penalty kick at Wembley. … Dennis Wise's right-footer from the free kick curled in towards the near post, Lawrie Sanchez … scored with a simple glancing header into the far corner."

- ↑ "World Notes Britain". Time. 1989-04-24. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,957533,00.html. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ "A hard lesson to learn". BBC. 1999-04-15. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/318497.stm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "Premier League vetoes the Intertoto Cup". London: The Independent. 1996-01-17. http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/premier-league-vetoes-the-intertoto-cup-1324474.html. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Babbington, Andrea (2000-06-01). "Dons have gone for a Burton". The Independent (London: Independent News & Media). http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/football-league/dons-have-gone-for-a-burton-714215.html. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "League warns Dons over move". BBC. 2001-08-10. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/1483683.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 "Dons get Milton Keynes green light". BBC. 2002-05-28. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/2012312.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 15.9 "Report of the Independent Commission on Wimbledon F.C.'s wish to relocate to Milton Keynes". The Football Association. http://www.wisa.org.uk/cgi/l/files/20020530_fa.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 White, Jim (2003-01-11). "Pitch battle". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2003/jan/11/clubsincrisis.sport. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Murdoch takes reins". BBC. 2002-06-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/2065340.stm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Moffitt, Alistair (2002-10-31). "Dons chief shrugs off lowest ever crowd". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2002/oct/31/newsstory.sport3. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Wimbledon go into administration". The Daily Telegraph (London: Telegraph Media Group). 2003-06-06. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/2405494/Wimbledon-go-into-administration.html. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Pryce, Robert (2003-09-29). "Wimbledon's happy ending is pure Hollywood". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2003/sep/29/match.burnley. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Milledge, Adrian (2004-04-07). "Wimbledon fall through trap-door". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2004/apr/07/match.sunderland. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Wimbledon to change name". BBC. 2004-06-21. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/3825865.stm. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 23.10 23.11 23.12 23.13 23.14 Roach, Stuart (2001-08-02). "Too big for their roots". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/1470328.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ "History in Milton Keynes". MK Web. http://www.mkweb.co.uk/Milton_Keynes_General/DisplayArticle.asp?ID=285. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Rundle, Richard. "Football Club History Database - Milton Keynes City". Football Club History Database. http://www.fchd.info/MILTONKC.HTM. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 26.11 26.12 26.13 26.14 26.15 26.16 26.17 26.18 26.19 26.20 26.21 Bose, Mihir (2001-08-16). "Hammam cast in villain's role as Dons seek happy ending". The Daily Telegraph (London: Telegraph Media Group). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/football/leagues/championship/3010879/Inside-Sport-Hammam-cast-in-villains-role-as-Dons-seek-happy-ending.html. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Conn, David (2005-02-26). "Spirit of the Beehive offers shining example to football's many drones". The Independent (London: Independent News & Media). http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/news-and-comment/david-conn-spirit-of-the-beehive-offers-shining-example-to-footballs-many-drones-484780.html. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Shaw, Phil (1997-06-12). "Hammam sells up without moving out". The Independent (London: Independent News & Media). http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/hammam-sells-up-without-moving-out-1255570.html. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ "Hammam sells up at Wimbledon". The Irish Times (The Irish Times Ltd.). 2000-02-26. http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/sport/2000/0226/00022600146.html. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ "Hammam's guard revealed to be convicted hooligan". The Independent (London: Independent News & Media). 2002-01-11. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/hammams-guard-revealed-to-be-convicted-hooligan-662831.html. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 31.9 "Submission by the Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association to the Independent European Football Review". Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association. 2006-03-12. http://www.independentfootballreview.com/doc/comments/33.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Pollock, Ian (August 2003). "Don roaming". When Saturday Comes. http://www.wsc.co.uk/content/view/2455/29/. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Pollock, Ian (July 2002). "Self development". When Saturday Comes. http://www.wsc.co.uk/content/view/2850/29/. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Stewart, Kris (March 2001). "Merton, not Milton". When Saturday Comes. http://www.wsc.co.uk/content/view/3363/29/. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ Samuel, Martin (2003-07-02). "Palios has duty not to bury head in the sand". The Times (London: Times Newspapers). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/sport/columnists/article1147321.ece. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Willacy, Gavin (February 2007). "Relocation, relocation". When Saturday Comes. http://www.wsc.co.uk/content/view/591/29/. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ "Move or die: 'A whole raft of us believe it is better to live, even if somewhere else'". The Independent (London: Independent News & Media). 2002-11-10. http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/football-league/move-or-die-a-whole-raft-of-us-believe-it-is-better-to-live-even-if-somewhere-else-603858.html. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "No name change for Wimbledon, despite the move". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). 2003-04-02. http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2003/apr/02/newsstory.sport. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "FA backs Wimbledon appeal". BBC. 2002-01-29. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/1741876.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ Conn, David (2009-04-28). "Tears of joy as AFC Wimbledon prove they are in the wider interest of football". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). http://www.guardian.co.uk/sport/blog/2009/apr/28/afc-wimbledon-blue-square-conference-south-champions. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ Hubbard, Alan (2002-01-20). "Mr Milton Keynes: 'Our door will be open to any club in trouble'". The Independent (London: Independent News & Media). http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/football-league/mr-milton-keynes-our-door-will-be-open-to-any-club-in-trouble-663980.html. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ↑ "Crozier 'appalled' by Dons move". BBC. 2002-08-22. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/2209767.stm. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ "City left fighting for their survival". Milton Keynes Today (Johnston Press Digital Publishing). 2003-06-05. http://www.miltonkeynes.co.uk/sport/City-left-fighting-for-their.528192.jp. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "City club on the brink of folding". Milton Keynes Today (Johnston Press Digital Publishing). 2003-07-03. http://www.miltonkeynestoday.co.uk/ViewArticle2.aspx?SectionID=416&ArticleID=554102. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 Watson, Stuart (2004-05-14). "The final whistle for Wimbledon?". Property Week (United Business Media). http://www.propertyweek.com/story.asp?sectioncode=39&storycode=3035621. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Moor, Dave. "Historical Kits Milton Keynes Dons". Historical Kits. http://historicalkits.co.uk/Milton_Keynes_Dons/Milton_Keynes_Dons.htm. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "AFC Wimbledon". AFC Wimbledon. http://www.afcwimbledon.co.uk/index.php?Psection_id=1. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ 48.00 48.01 48.02 48.03 48.04 48.05 48.06 48.07 48.08 48.09 48.10 48.11 48.12 48.13 48.14 48.15 48.16 48.17 48.18 48.19 48.20 48.21 Moor, Dave. "Historical Kits Wimbledon". Historical Kits. http://www.historicalkits.co.uk/Wimbledon/Wimbledon.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ "Wimbledon move gets go-ahead". BBC. 2003-09-19. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/3114084.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ "First turf cut for Dons' stadium". BBC. 2005-02-17. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/beds/bucks/herts/4274475.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ Sinnott, John (2005-12-05). "MK Dons fix stadium launch date". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/4501170.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ "Milton Keynes stadium is on track". BBC. 2007-02-15. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/6366309.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ "Dons open stadium against Chelsea". BBC. 2007-07-19. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/teams/w/wimbledon/6906212.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "Open Letter To The Football Association". Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association. 2003-05-28. http://www.wisa.org.uk/cgi/l/articles/index.cgi?action=show&id=343. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 "Interview & Comment: Pete Winkelman". FourFourTwo (Haymarket Group). 2004-11.

- ↑ "AFC Wimbledon Honours". AFC Wimbledon. http://www.afcwimbledon.co.uk/honours.php?Psection_id=4&Psub_section_id=7&squad=. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 "History and Honours of Wimbledon FC returned to Merton". Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association. 2007-08-02. http://www.wisa.org.uk/cgi/l/articles/index.cgi?action=show&id=558. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ "It’s come home". Merton Borough Council. 2008-04. http://www.merton.gov.uk/my_merton_issue_28_final_proof.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "WISA launches the Wimbledon Old Players Association". Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association. 2005-09-12. http://www.wisa.org.uk/wopa/news1.html. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ "Wimbledon Masters Are Back". Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association. 2006-05-23. http://www.wisa.org.uk/wopa/news7.html. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ Stockford, Tara. "Wombles football mascots". Tidy Bag - The Online Wombles Museum. http://www.tidybag.co.uk/memorabilia/wombles-football-mascots/. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ "Financing a New Stadium". Wimbledon F.C.. 2003. http://www.mkweb.co.uk/mkdons/DisplayArticle.asp?ID=12192. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 "Milton Keynes Dons/AFC Wimbledon". European Football Statistics. http://www.european-football-statistics.co.uk/attnclub/wimb.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 "WISA - A Brief History". Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association. http://www.wisa.org.uk/history/index.html. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 "About the Trust". AFC Wimbledon. http://www.afcwimbledon.co.uk/aboutthetrust.php?Psection_id=10. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ "Rivalry uncovered". Football Fans Census. December 2003. http://www.footballfanscensus.com/issueresults/Club_Rivalries_Uncovered_Results.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Jones, Marc. "Roy Law". FOTO. http://afcw.foto.co.uk/players?ID=Roy%20Law&uid=0. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ Jones, Marc. "Eddie Reynolds". FOTO. http://afcw.foto.co.uk/players?ID=Eddie%20Reynolds&uid=0. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Jones, Marc. "Ian Cooke". FOTO. http://afcw.foto.co.uk/players?ID=Ian%20Cooke&uid=0. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "Alan Cork". Sporting Heroes. http://www.sporting-heroes.net/football-heroes/displayhero_club.asp?HeroID=16869. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 71.4 71.5 "MK Dons (formerly Wimbledon) all time records". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. http://www.soccerbase.com/team_records.sd?teamid=2812. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "Hartson joins Wimbledon for £7.5m". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). 1999-01-15. http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/1999/jan/15/newsstory.sport9. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ Nixon, Alan (2000-07-06). "Newcastle beat Tottenham to sign £7m Cort". The Independent (London: Independent News & Media). http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/premier-league/newcastle-beat-tottenham-to-sign-pound7m-cort-709397.html. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 "Wimbledon : Records". Statto. http://www.statto.com/football/teams/wimbledon/records. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ Shaw, Phil (1995-06-26). "No picnic for English clubs by the sea". The Independent (London: Independent News and Media). http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/no-picnic-for-english-clubs-by-the-sea-1588438.html. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ↑ "Wimbledon Official Site". Wimbledon F.C. (via Internet Archive). 2004-04-05. http://web.archive.org/web/20040412000945/www.wimbledon-fc.premiumtv.co.uk/page/Home/0,,10420,00.html. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Hambly, Dave. "1930 to 1939". Historical Dons. http://historicaldons.com/1930.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 Hambly, Dave. "1940 to 1949". Historical Dons. http://historicaldons.com/1940.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 79.3 Hambly, Dave. "1950 to 1959". Historical Dons. http://historicaldons.com/1950.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ Hambly, Dave. "1960 to 1969". Historical Dons. http://historicaldons.com/1960.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 81.3 81.4 81.5 81.6 81.7 Hambly, Dave. "1970 to 1979". Historical Dons. http://historicaldons.com/1970.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Hambly, Dave. "1980 to 1989". Historical Dons. http://historicaldons.com/1980.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "Manager History for Wimbledon". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. http://www.soccerbase.com/manager_history.sd?teamid=2812. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

External links

- The official website of AFC Wimbledon

- The Wimbledon Old Players Association

- The official website of Milton Keynes Dons F.C.

- Statistics for part of Wimbledon FC's existence

- Wimbledon at the Football Club History Database

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||